Along with Theodore Roosevelt, Wilson is one of two figures credited with the establishment of the modern presidency and the ascendance of American leadership on the international stage. Following Wilson’s tenure, the president would not only be considered head of the political party but also as manager of the nation's interests—at home and abroad—independent of the party and Congress.

Entering the War

When World War I broke out in Europe in 1914, Wilson’s primary goal was to maintain American neutrality and to help broker peace between the warring parties.

While his isolationist policies succeeded at first – helping him win reelection in 1916 with the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War” – Wilson was wary of the risks of an Allied defeat. To this day, historians debate the complex circumstances that led to the declaration of war in April 1917 even as many Americans continued to support neutrality.

Before American intervention, Germany’s ongoing U-boat attacks on American ships, most famously the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915, did not dramatically shift popular support in favor of joining the Allied powers. However, when Germany tried to induce Mexico in what is now called “the Zimmerman telegram” to attack the United States, Wilson called upon Congress to “make the world safe for democracy” and declare war.

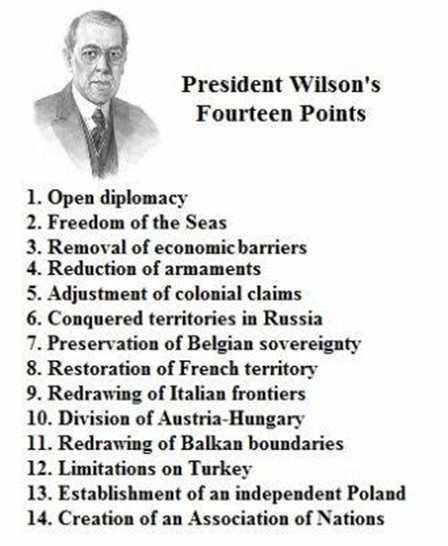

As Commander-in-Chief, Wilson led America to victory in a mere 18 months. Relying on a largely Black and female labor force, he harnessed the nation’s immense industrial power for the war effort. In passing the controversial Alien and Sedition laws, and launching a racist anti-German propaganda machine, the administration pushed for public support. And, as victory came into sight in January 1918, Wilson put forth his vision for a new world order in his Fourteen Points for Peace – a plan that would profoundly shape international politics and America’s status as a world leader for decades to come. This needs further integration and analysis about the impact of WW’s international policies.

The "14 Points"

The Fourteen Points called for reforms such as an end to secret agreements, free trade, and creating an intergovernmental organization addressing issues using diplomacy instead of military force called: The League of Nations. Most notably, this Wilsonian International Policy emphasized the right of individual national to self-determination. However, Wilson’s view of the right to self-determination was not universal. His view of a racial hierarchy that influenced his domestic policy also influenced his foreign policy so that his belief in the right to self-government was largely limited to European nations.

Peace

At the Paris peace conference in 1919, Wilson moved the seat of the presidency to Paris for six months while he commanded the attention of the world. He drew up terms of peace including his design for a League of Nations. Wilson took direct personal control of American foreign policy, which he believed was constitutionally mandated. He personally attended meetings and negotiations and penned his approval of the Terms of Peace and the Covenant of the League of Nations. But Wilson's biggest fight was yet to come.

Back in the United States, the Senate had reservations over the League, reservations that still echo today, about the U.S losing sovereignty and becoming the "policeman of the globe." They failed to ratify the treaty, despite two attempts and a cross-country trip by the president to bring his argument directly before the American people.

Despite his failure to get the U.S into the League of Nations and to secure all of the 14 Points in the Treaty, Wilson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize as the founder of the League.

Legacy of Wilsonianism

Wilson commanded a presence on the world stage that no other American president had ever achieved. He championed a new way of doing diplomacy, throwing away the old idea of “To the victor go the spoils, and instead asking for “peace without victory” He was showered with flowers and cheers in the streets of Paris, London and Rome. He became the first American president to be received at Buckingham Palace, and to have an audience with the Pope. The United States moved to the forefront of world powers, and Wilson’s view of American foreign policy, now known as “Wilsonianism,” continues to influence debates and ideas about America’s role as a global leader and the right of national self-determination.

The Pan African Congress at Paris and Racial Equality on the World Stage

The promise of self-determination fueled a growing, global, and diverse Pan-African movement. At the end of the war, leaders of the movement hoped to secure those rights for African nations under European colonial rule and African Americans subject to the brutalities of Jim Crow.

As Wilson met with world leaders at Versailles, NAACP leaders including W.E.B. DuBois and Ida Gibbs Hunt who organized a Pan-African Congress in Paris with 57 delegates representing 15 countries. The Congress sought to influence the peace talks, lobbying for the establishment of a new state in Africa to be formed out of Germany’s former colonies, seeking a gradual abolition of European colonialism and Africa, and asserting a leading role for Black leaders in international relations. Wilson’s racism at home, however, impacted his leadership abroad and the Pan African Congress garnered little attention from those at Versailles.

The signing of the Peace Treaty, however, did not mean peace and prosperity at home for all. The African American soldiers who had fought “to make the world safe for democracy” returned to a home country that failed to secure their democratic rights. The wartime rhetoric of democracy, freedom, and self-determination would imbue the Civil Rights movements for decades to come.