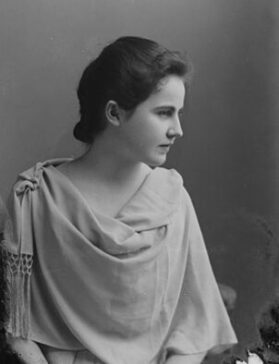

About Edith Wilson

As the longest resident of 2340 S Street, Edith Wilson defined its legacy. Her bequest of the home to the National Trust for Historic Preservation stipulated that the Kalorama mansion stand as a memorial to her husband. It was that directive that has shaped the stories told and the ones we will continue to tell in the years to come.

Edith Bolling was born in Wytheville, Virginia in 1872. The 7th of 11 children to a prominent Virginia family, Edith was a direct descendant of the first European settlers that arrived on the Powhatan land of Tsenacomoco - which the English settlers named “Virginia.” In fact, Edith also claimed to be a direct descendant of the storied daughter of the Powhatan chief, Pocahontas [birthname ‘Amonute’]. A portrait of Pocahontas hangs in Edith's bedroom at the S Street House along with a vast collection of Pocahontas-related objects collected by Edith.

At the age of 24, Edith married a wealthy Washington, D.C. jeweler named Norman Galt. Galt died in 1908 but Edith maintained ownership of her husband’s business and established her place among the capital’s social elite. So it happened that in 1915, less than a year after Woodrow Wilson’s first wife, Ellen Axson Wilson, died, Edith’s connections led to her a chance meeting with the President. The pair quickly (and very quietly) fell in love and were married in a small private ceremony on December 18, 1915, at her home at 1308 20th Street, near Dupont Circle, in Washington, D.C.

Edith and Woodrow Wilson’s relationship was defined as much by their devotion to one another as it was to their intellectual connection. Throughout their courtship, Wilson sent Edith daily, detailed updates on policy issues and awaited her notes and commentary with every reply. In fact, many advisors were rumored to be wary of Edith’s influence over the President. To this day, speculations persist that Wilson came out in support of the New Jersey referendum in support of women’s suffrage on the eve of his marriage in part to assuage those concerned that his soon-to-be anti-suffragist wife was shaping his policy decisions.

Edith’s central role in her husband’s presidency ultimately became her legacy. When Woodrow Wilson endured his second stroke in 1919, Edith took on the role of gatekeeper to the Oval Office. Insistent that her husband’s dire illness be kept secret, Edith safeguarded his condition from even his closest advisors and demanded that ALL presidential business be reviewed by her before being brought to her husband’s attention. While some have argued that in those months Edith took up the mantle of President of the United States —and was therefore the first woman to do so—evidence and her own memoirs suggest that she did not act to directly shape policy, rather she simply determined what issues were important enough to be brought directly to her husband’s attention. More often than not, most were sidelined until the President more fully recovered.

Edith’s own political views were, like her husband’s, largely shaped by her southern upbringing. Not only did she oppose women’s suffrage, but she was also an active member of the “Confederate Memorial Literary Society,” which supported the effort to erect Confederate memorials throughout the country and to push forward the false “Lost Cause” narrative of the South in the Civil War.

Edith remained a prominent member of D.C. society even after her husband’s death. She continued to be a beloved hostess to diplomates and D.C. political leaders making the S Street house a center of D.C. social life.

You can visit the Edith Bolling Wilson Birthplace Museum in Whytheville, VA today. Watch this introduction video about the site.