The Woodrow Wilson House

A century after Woodrow Wilson left office, his policies and legacy continue to animate our national conversations about American foreign policy and the meanings of progressivism and democracy and to re-analyze the effects of his failures in the area of race relations. Wilson’s time in the White House – and its impact generations after – is rife with paradoxes and contradictions. His progressive “New Freedom” platform envisioned an active federal government as a force for equity, and yet, that vision actively excluded African Americans. Indeed, his often deliberate inaction on racial justice brought to bear the limits of these progressive ideals. Celebrated for advancing democracy and freedom abroad, many of Wilson’s domestic policies entrenched racial segregation and injustice at home, curtailing the rights and privileges of African Americans, women, and immigrants.

An accurate and full accounting of the Wilson Era reveals the systemic injustices we continue to confront to this day. At the same time, understanding Wilson’s leading role in defining and leading a new dawn in 20th-century international relations is vital to rethinking those dynamics in the 21st century. The Woodrow Wilson House is committed to listening to as well as leading these important civic discussions. As a hub for both public museum exhibitions and scholarly engagement with Wilson’s legacy as well as the Progressive Era, the Wilson House aims to be a space of reconciliation and healing through an honest, dynamic exploration of the past and the present.

A History of the S Street Mansion

On March 4, 1921, Woodrow and Edith Wilson moved out of the White House and into their new home – just a mile and a half away – at 2340 S Street, N.W. in D.C.’s Kalorama neighborhood. The former president lived at S Street house until his death in 1924. Edith called the mansion home until her passing in 1961, at which time she bequeathed the house and its furnishings to the National Trust for Historic Preservation to serve as a monument to President Wilson.

Completed in 1916, the Wilson’s new, very modern home and stately gardens were designed in the Georgian Revival style by renowned architect Waddy Butler Wood—who also designed the home next door. Originally built as the private residence for Henry Parker Fairbanks, an executive at the Bigelow Carpet Company, the S Street house combines classic design with then-modern necessities. Along with a marble entryway and grand staircase, Palladian window, book-lined study, and a solarium overlooking the formal garden, the house also boasts a dumbwaiter and butler’s pantry, a telephone intercom system, and a kitchen stocked with the latest gadgets of the day.

The S Street house has been maintained much as it was in 1924, including furniture, art, photographs, state gifts, and the personal effects of President and Mrs. Wilson. The drawing room includes a century-old Steinway piano that President Wilson had in the White House, a framed mosaic that he received on his trip to Italy in 1919 from Pope Benedict XV, and a wall-sized Gobelin tapestry presented by the people of France following World War I.

Before President and First Lady Barack and Michelle Obama, the Wilsons were the only President and First Lady to make Washington their permanent home after leaving office. In retirement, the Wilsons received dignitaries and guests at the home, including former British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and former French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau.

On the fifth anniversary of Armistice Day, November 11, 1923, the S Street House became the site of a landmark historic event when the former President made the first nationwide remote radio broadcast to commemorate the day.

The House opened as a museum in 1963.

Residents of S Street

The story of the S Street House is as much of the people who lived and worked alongside the Wilsons as it is about the former President and First Lady. Isaac and Mary Scott were the Butler and Housekeeper for the Wilsons, living in the house for a decade but continuing to work there into the 1950s.

Isaac Spencer Scott (1875–1959), a native Washingtonian, married Mary Ashley Sloane (1882–1968), of Washington, Virginia, in 1908. For 20 years, Isaac worked as a porter for the Galt & Bro. Jewelers owned by Edith Wilson’s first husband, Norman Galt. In 1921, the Scotts joined the staff at the Wilsons’ new home on S Street. Though the couple would purchase a home at 4434 Hunt Place in DC’s Deanwood neighborhood in 1931, they continued to work at S Street into the 1950s. Far more than staff who maintained the home, Isaac and Mary were caretakers for the ailing President and managed the S Street House for more than three decades.

Along with the Scotts, Edith Wilson's brother John Randolph Bolling also lived at 2340 S Street, occupying the 3rd floor bedroom that is now the museum’s executive director's office. Mr. Bolling worked as President Wilson’s private secretary.

Part-time staff people also commuted to S Street when needed. In 1921, these included Mr. George Howard, the chauffeur, Mr. Rupple, the night nurse, a laundress once a week and probably a cook for all but the simplest meals. As Wilson's health deteriorated there were additional nurses who rotated in and out, their imprint on the house remains in our collection of modern medical devices on display.

In later years, various relatives of Mrs. Wilson lived with her at different times. The museum is committed to continuing to research the histories and experiences of these individuals.

The Kalorama Neighborhood

In the decades following the Civil War, Washington D.C. morphed from a small, contained city to a sprawling metropolis. The growth of the federal government, coupled with new public transportation technologies spawned rapid development that pushed the city’s boundaries outwards.

In the 1890s, the Kalorama neighborhood, situated in D.C.’s Northwest quadrant, emerged out of this building boom.

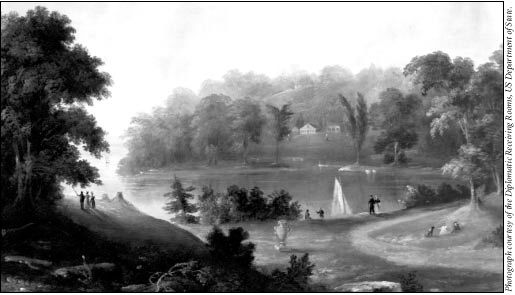

Kalorama sits on the ancestral lands of the Anacostans (also documented as Pamunkey Indian Tribe Nacotchtank). It was “a lovely seat...on a high hill commanding a most extensive view of the Potomac,” as Thomas Jefferson put it in a letter to his friend Joel Barlow, a popular poet and a diplomat. Barlow purchased the estate and renamed it “Kalorama” -- Greek for “beautiful view.”

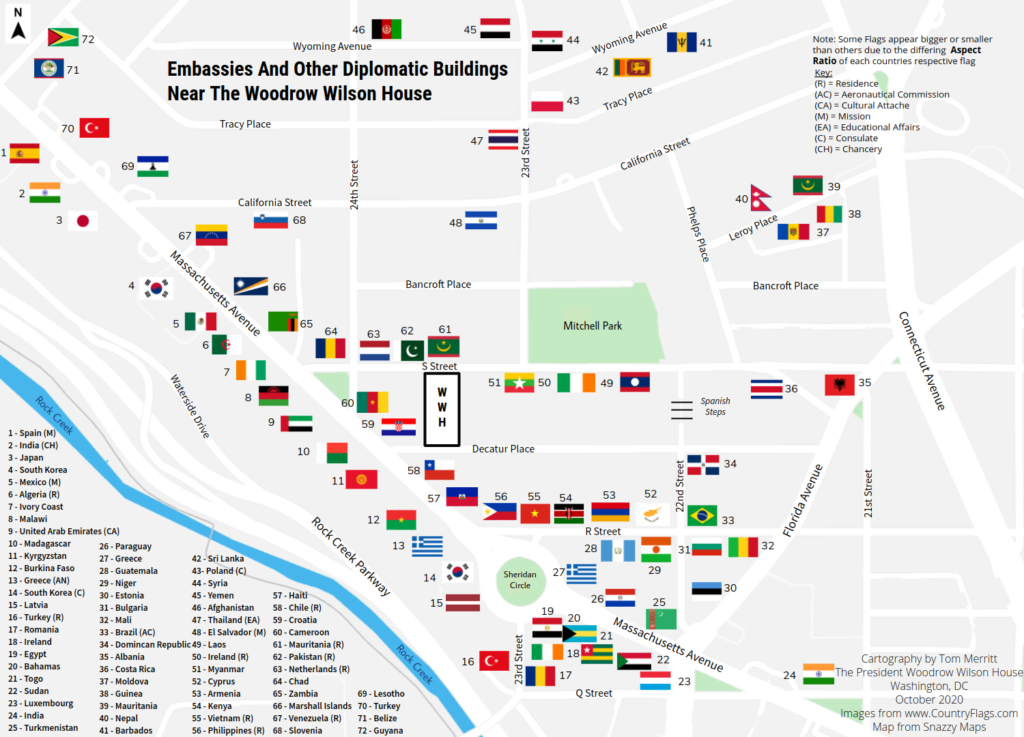

Upon his death in 1812, Barlow’s widow sold the property but it changed hands many times. During the Civil War there was a hospital for smallpox patients on the property which took advantage of the cooling breezes and the good view on the hillside overlooking Washington. Over the years, the neighborhood held the homes of several Presidents in addition to Woodrow Wilson, including Herbert Hoover, William Howard Taft and a young Franklin Roosevelt, as well as Supreme Court Justices, Members of Congress, writers, and other luminaries, including President and First Lady Barack and Michelle Obama. The first embassy, Thailand, was built in Kalorama in 1920, and the neighborhood’s “Embassy Row” is now the site of embassies and diplomatic residences, as well as private homes and museums.

And yet, throughout the first several decades of its development, the beautiful, storied neighborhood in the nation’s first majority-Black city, remained inaccessible to most of D.C.’s Black residents.

The building of Kalorama reflected the larger trends of post-Reconstruction Washington D.C. As historians Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove explain, prior to and immediately after the Civil War, all four of the city’s quadrants (NW, SW, NE, and SE) were racially and economically diverse with wealthy White politicians living on the same streets as poor immigrants and middle-class Black residents. The cementing of Jim Crow, bolstered by the Wilson administration’s segregation of the federal government, turned 20th century D.C. into a starkly racially divided urban landscape.

By the 1920s, just as the Wilson’s moved to S Street, restrictive covenants had institutionalized neighborhood segregation in the capital. These covenants -- private contracts among neighborhood residents barring the sale of homes to African Americans as well as Jews, Catholics, and Asians, limited minority access to improved housing and city resources. The landmark 1926 case, Corrigan v. Buckley, established the legality of these contracts by citing the D.C.’s existing policies segregating schools and recreational facilities. The house at the center of this legal battle was just a few blocks East of the Wilson House on S Street and 17th.

Isaac and Mary Scott

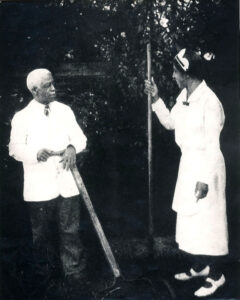

Isaac (1875-1959) and Mary Scott (1882-1968) served the Wilsons at their home on S Street for many years. Isaac Spencer Scott was born and raised in Washington, DC and for 20 years worked as a porter for the Galt & Bro. jewelry store owned by Edith Bolling’s first husband, Norman Galt. In 1908 Isaac married Mary Ashley Sloane of Washington, VA. The Scotts joined the Wilsons’ service at S Street in March 1921 and lived on the 4th floor.

When they departed the White House, the Wilsons were forced to leave Brooks, the White house steward and valet to the President, behind. “How to replace him seemed a real problem,” writes Edith in her memoir. “However fate was kind. I had been able to get a couple I had long known and to whom I here pay a tribute of gratitude and affection … I count them high on my list of this world’s blessings.”

Mary Scott ca 1908. (Image courtesy of the Sloane Family)

Isaac Scott assisting the disabled Wilson at S Street in 1922.

Explore the Neighborhood

Kalorama is bordered by Connecticut Avenue, Florida Avenue, 22nd Street, P Street, Rock Creek Park and includes part of Massachusetts Avenue. It is easily accessible from Washington’s Metro system.

Waddy Wood Walking Tour

As you explore the beautiful Kalorama neighborhood, learn about the history and residents of thirteen houses designed by the famous architect of the Woodrow Wilson House, Waddy Butler Wood.

Book NowKalorama Audio Tour

Explore the history and cultural diversity of the magnificent Kalorama neighborhood; all you need is your cell phone and our downloadable map to navigate! Listen on your phone to stories from those who know this neighborhood best: diplomats, residents and friends of the Wilson House, with guest appearances from famous Washingtonians.

Book Now